Difference Between Fresh and Frozen Embryo Transfer: Which Is Better for You?

Deciding between a fresh and a frozen embryo transfer can feel like a challenge. Both options begin the same way: eggs are collected, fertilised in the lab, and carefully watched as they grow. From that shared starting point the paths diverge.

In a fresh transfer the best-looking embryo goes back into your uterus only a few days after retrieval whereas in a frozen transfer it is stored in liquid nitrogen and returned in a later cycle which could sometimes be weeks, sometimes years down the line.

Success rates for each method are now neck-and-neck, so the real question becomes which timing, hormonal setting, cost profile, and risk level match your circumstances. The overview below breaks the decision into practical questions, answers them so you can discuss with your care team.

Difference Between Fresh Vs Frozen Embryo Transfer

| Factors | Fresh Embryo Transfer | Frozen Embryo Transfer |

|---|

| When is the embryo placed? | 3–5 days after retrieval, same cycle | Weeks to years later, separate cycle |

| Hormone environment | Elevated from stimulation | Near-natural or mildly supplemented |

| Need for extra retrieval | None this cycle; new retrieval if you want siblings | None until stored embryos are used up |

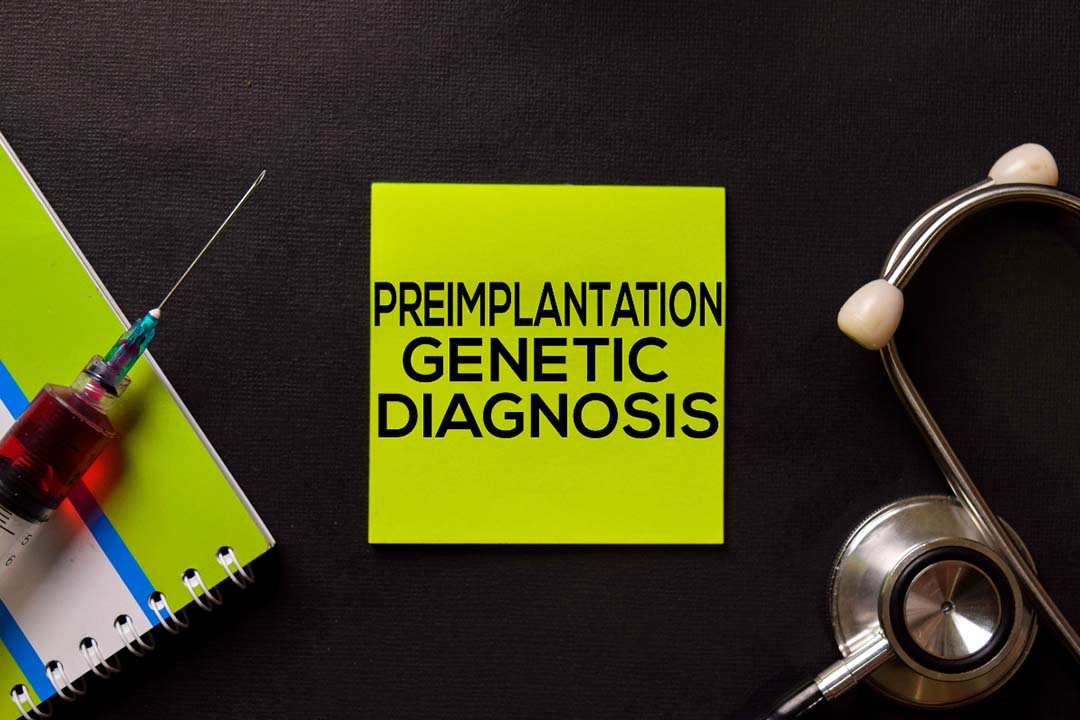

| PGT compatibility | Requires freeze anyway if chosen | Built-in—test, then thaw when ready |

| OHSS risk | Higher, especially in PCOS | Much lower |

| Cost per additional attempt | High (new stimulation) | Lower (lining meds only) |

| Logistics | One concentrated month | Flexible timing, additional visits |

| Ideal candidate | Younger, limited embryos, no OHSS risk | Anyone needing genetic testing, PCOS, or desire for scheduling control |

What Exactly Happens During an Embryo Transfer?

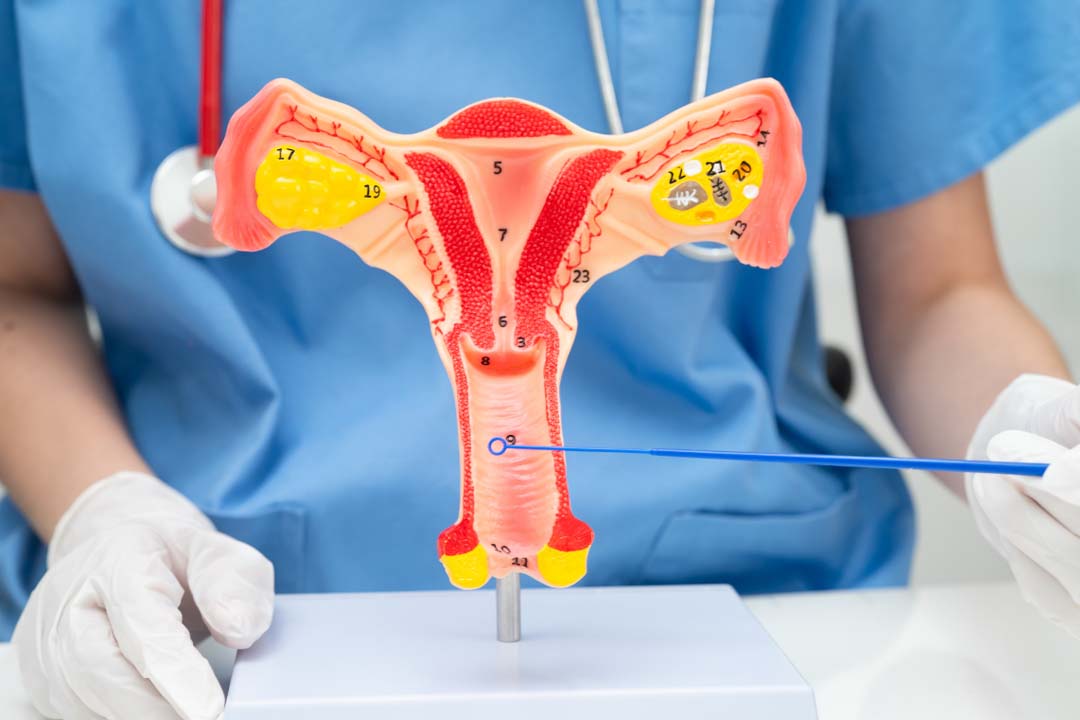

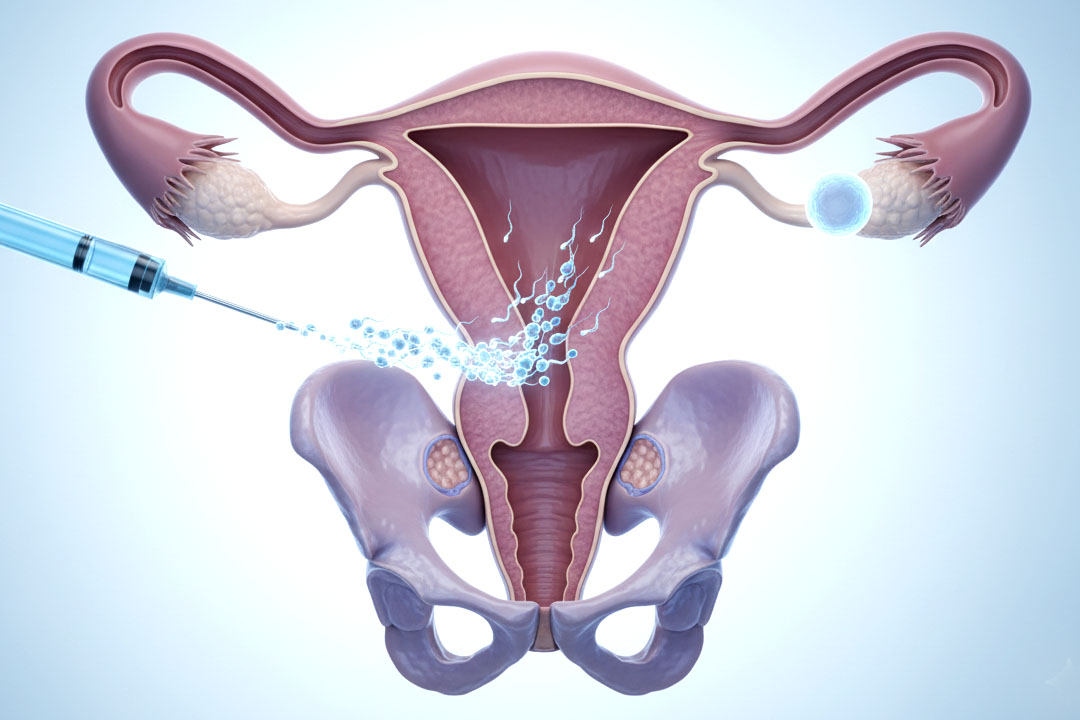

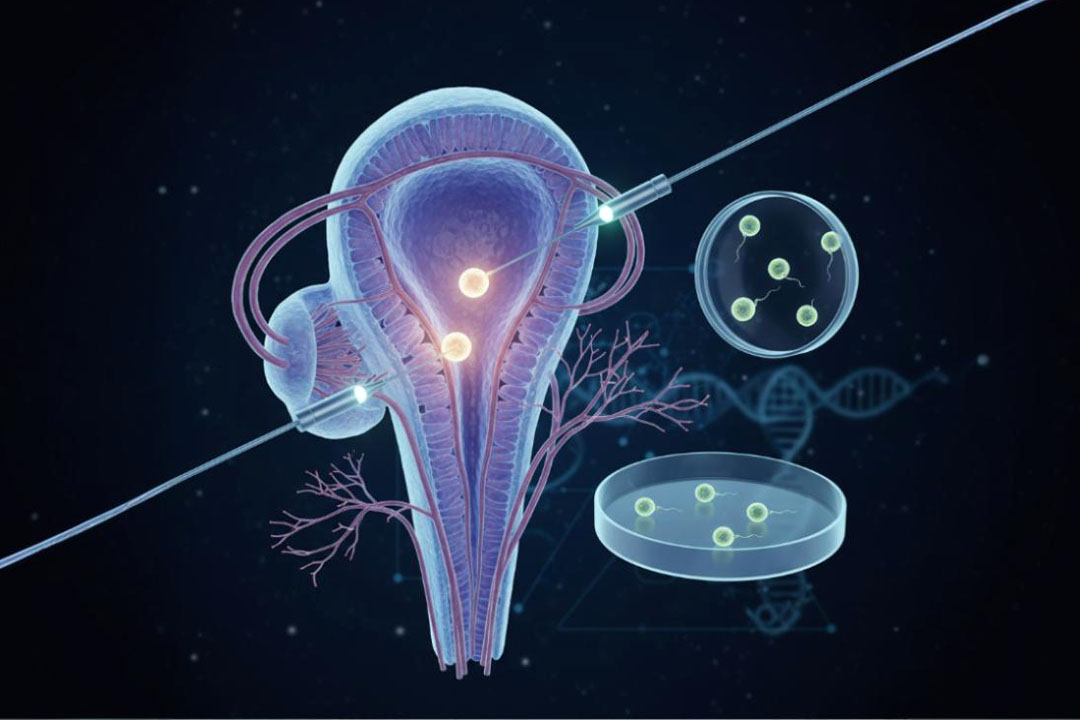

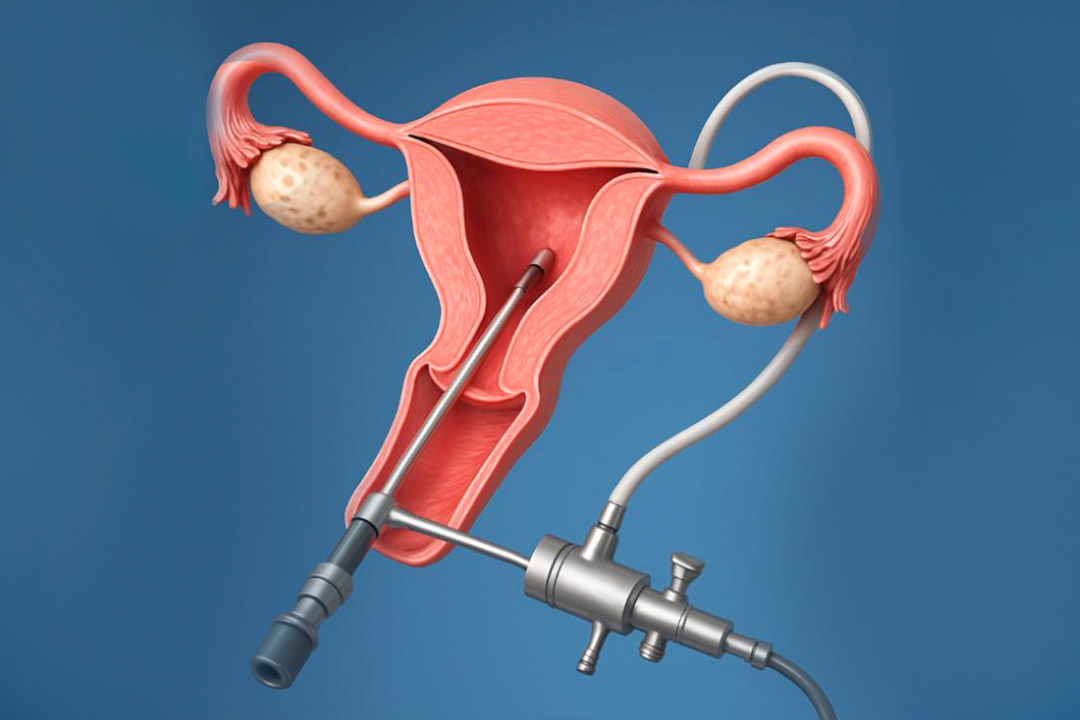

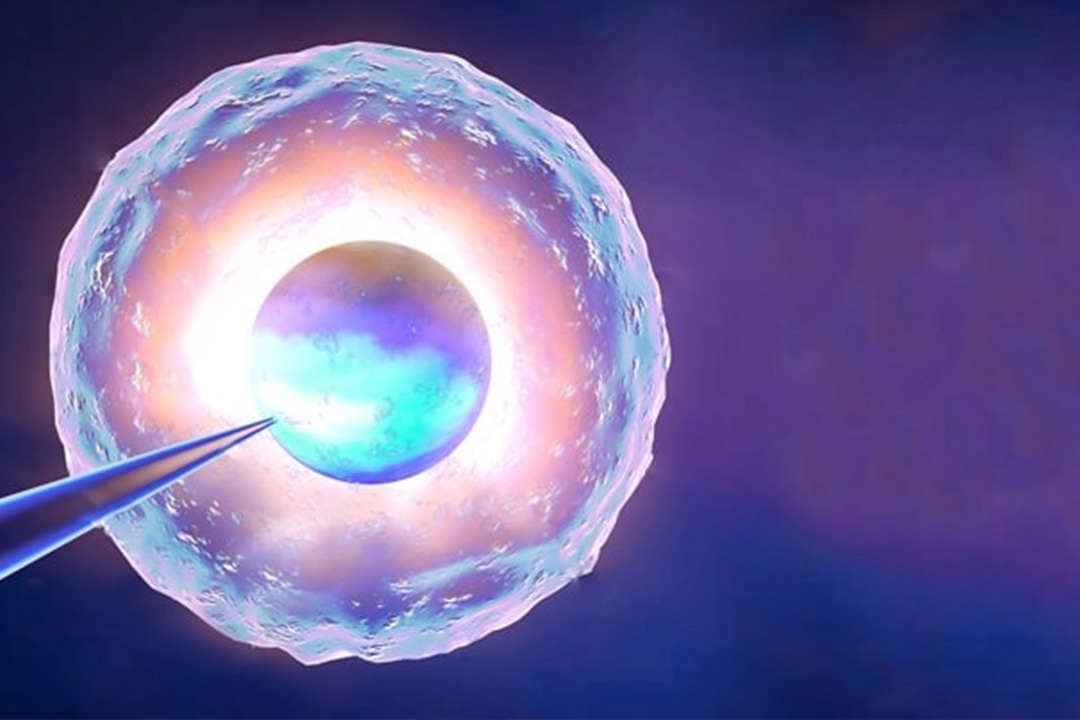

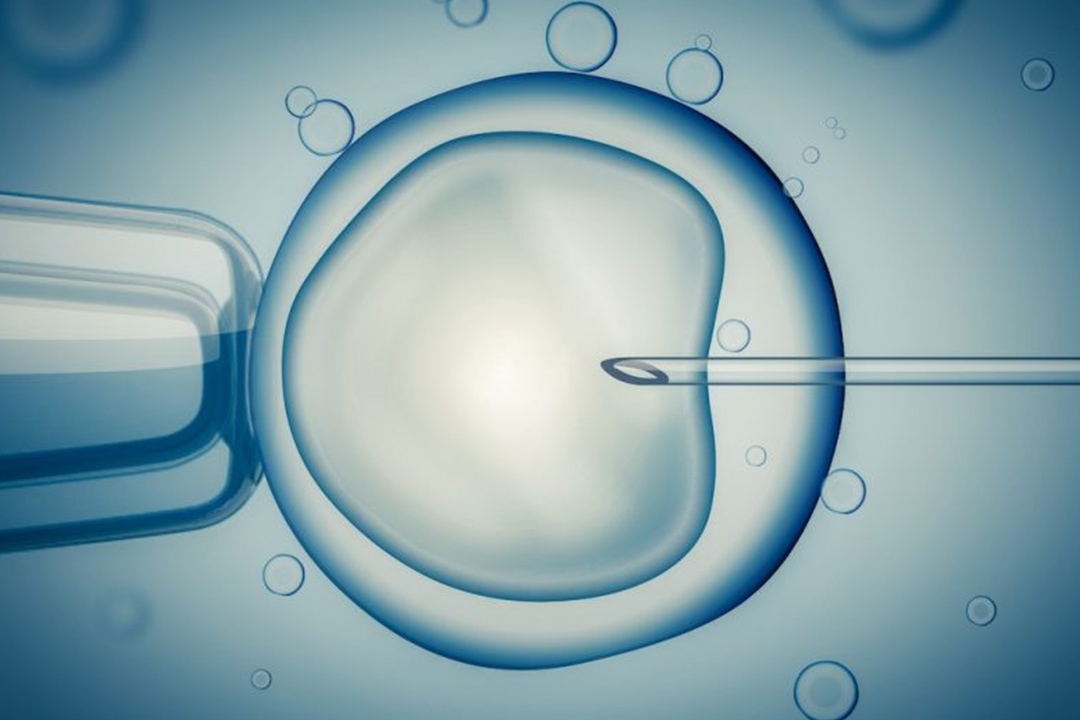

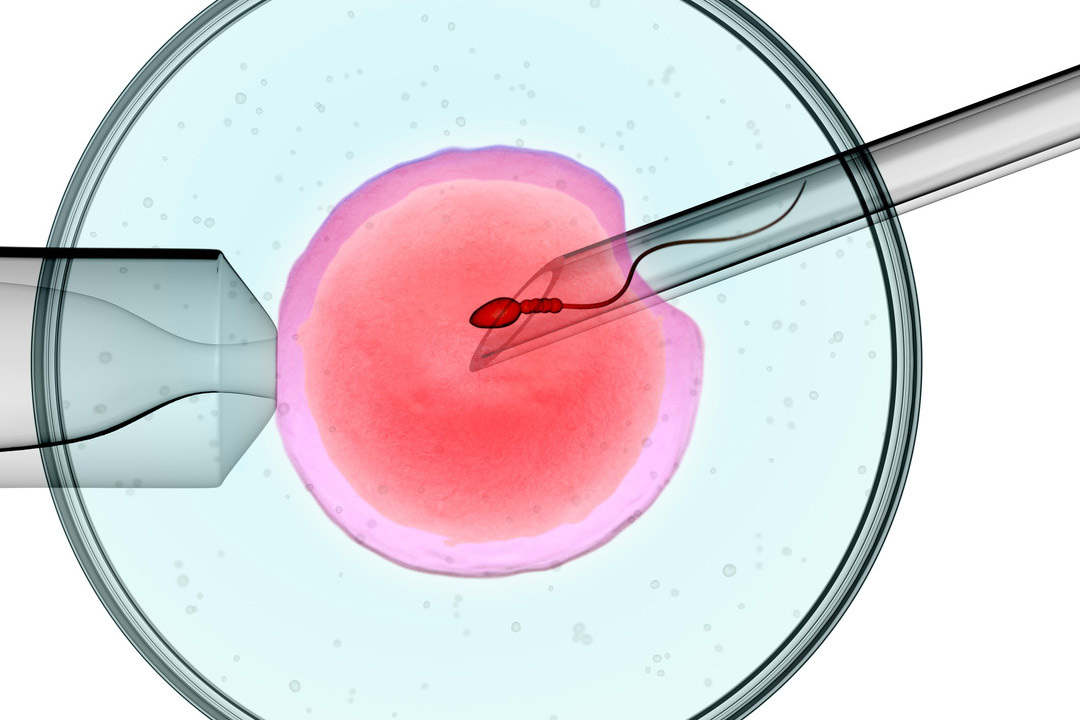

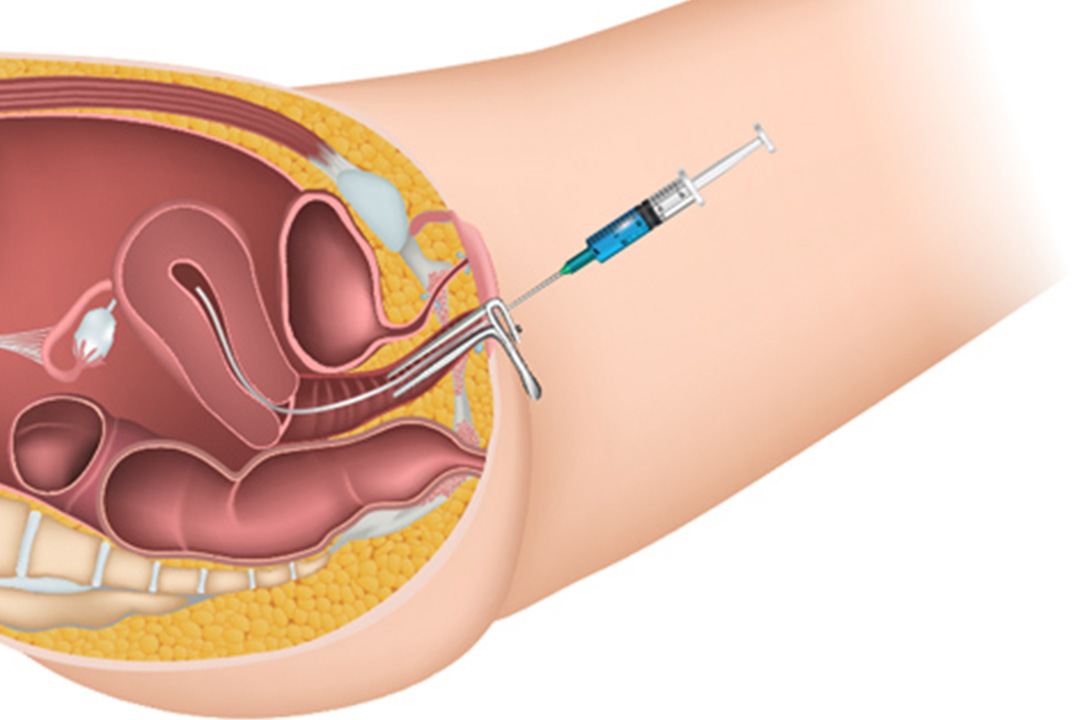

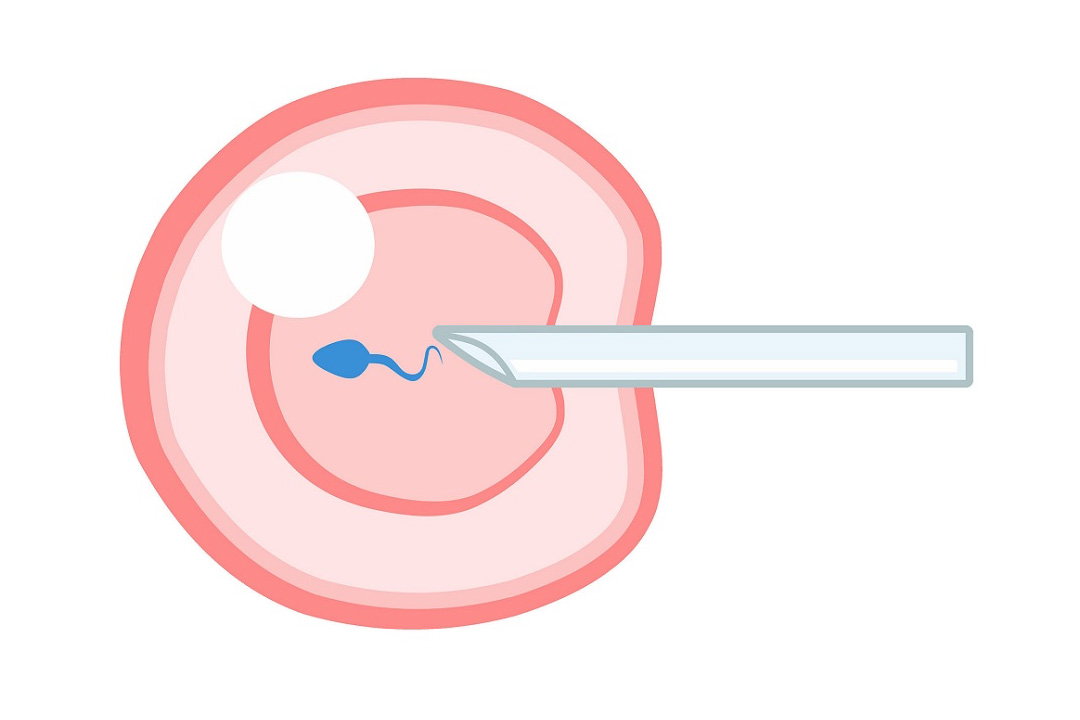

The transfer itself is a quick outpatient procedure: a thin catheter carries one or two embryos through the cervix and places them against the uterine lining. Ultrasound guidance helps the doctor nudge the tip to the right depth.

You stay on the table for a short rest and can usually walk out within half an hour. Because the catheter bypasses the fallopian tubes, success depends on two main factors:

(1) embryo quality

(2) endometrial readiness

Whether the embryo was just created or thawed from storage does not change the mechanics of this moment; it only changes how you reached it.

How Does a Fresh Transfer Go from Retrieval to Implantation?

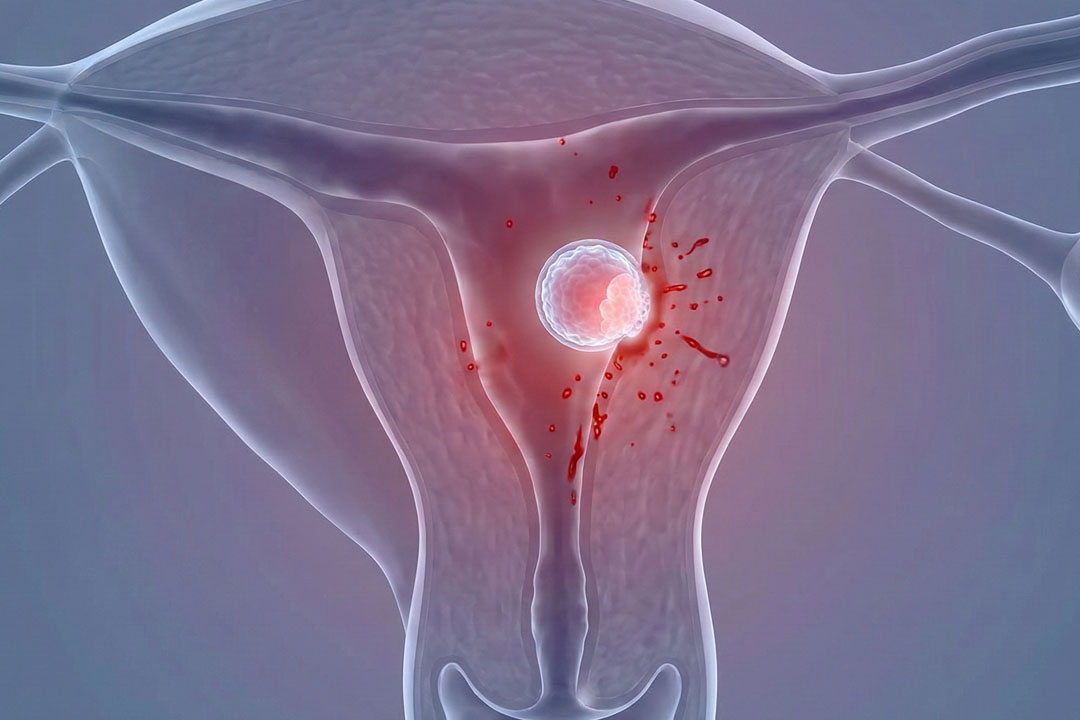

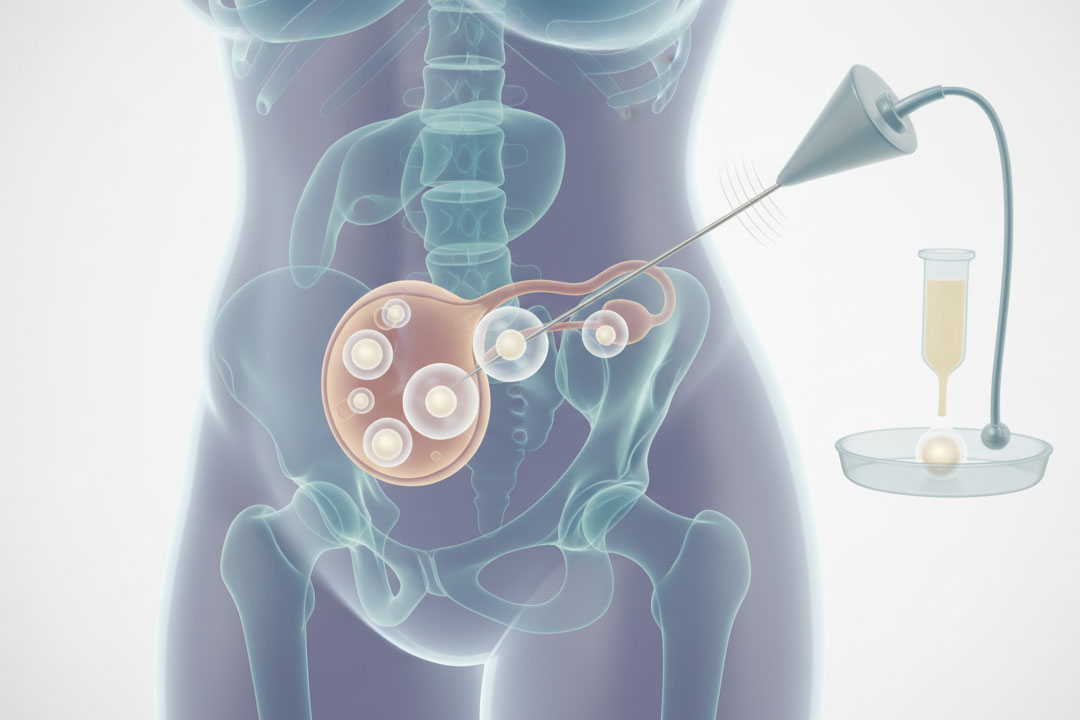

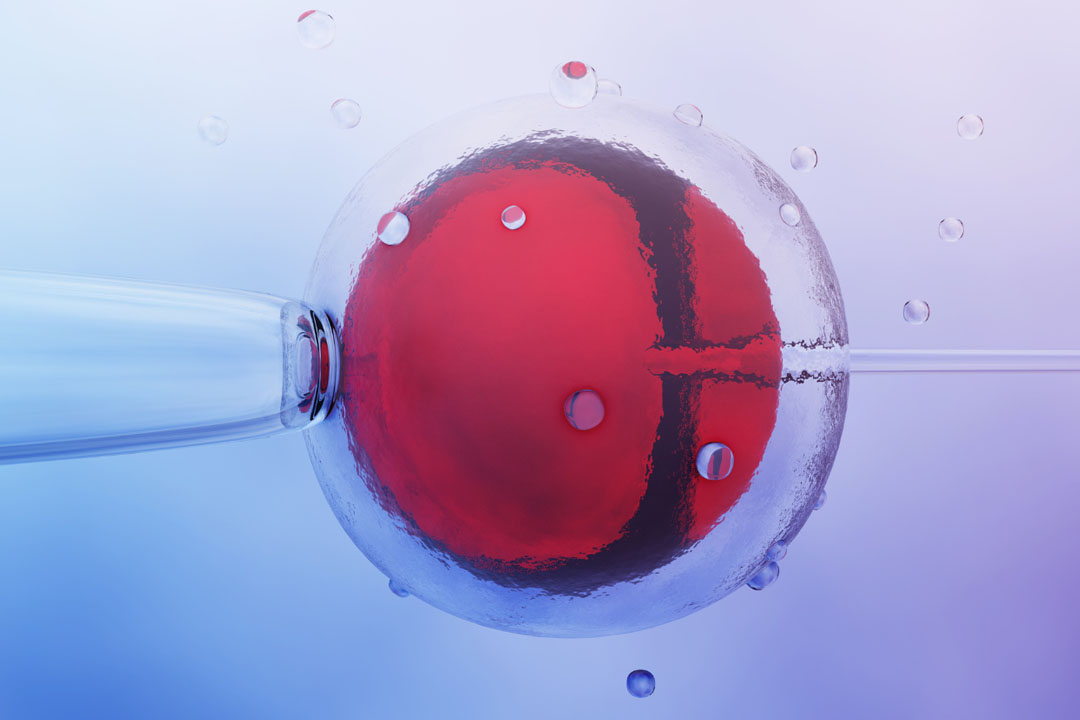

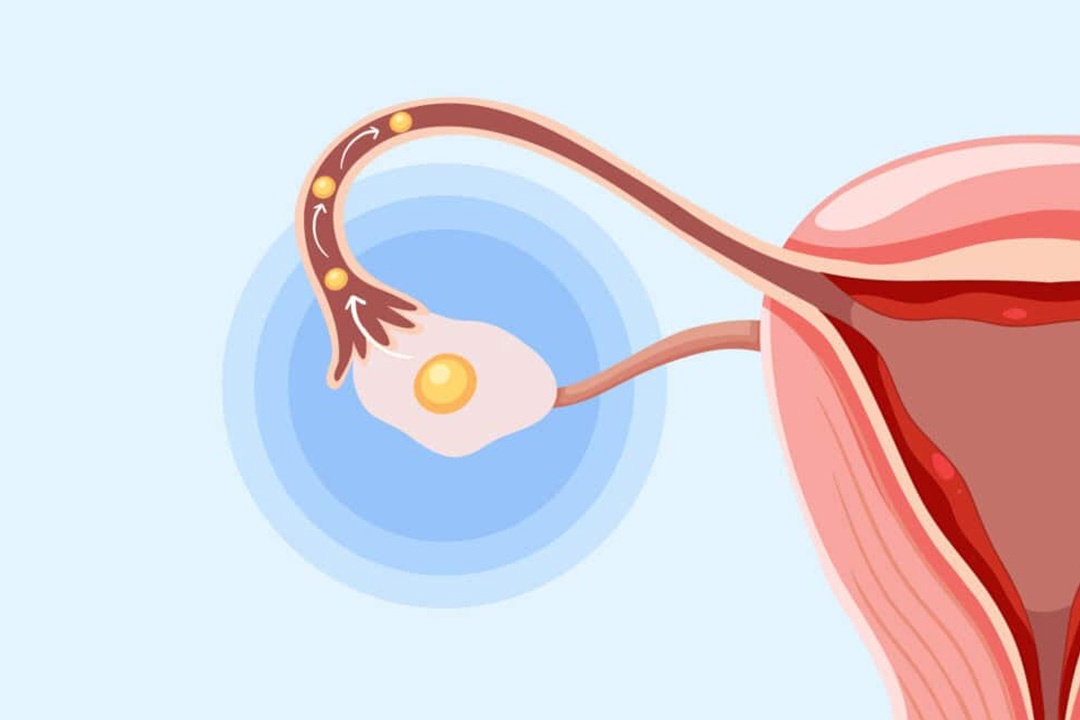

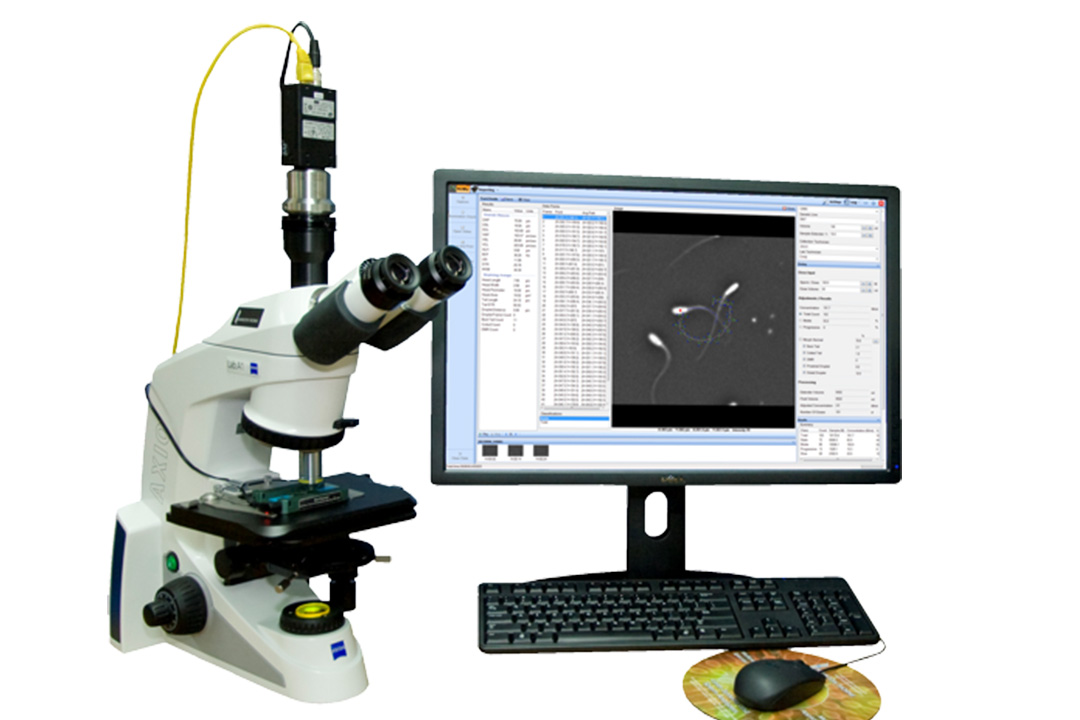

In a fresh cycle you move fast. After roughly ten days of ovarian stimulation, your eggs are retrieved under light anaesthesia. The lab fertilises them, and fertilised eggs that divide normally are called embryos.

On day 3 or day 5 the best embryo or sometimes two are selected. Because your ovaries have been heavily stimulated, your oestrogen and progesterone levels are still higher than they would be naturally.

You will take supportive hormones, but you do not need to repeat the retrieval. Everything happens within one menstrual cycle, which can feel efficient if you are eager to move ahead.

How is a Frozen Transfer Different in Timing and Preparation?

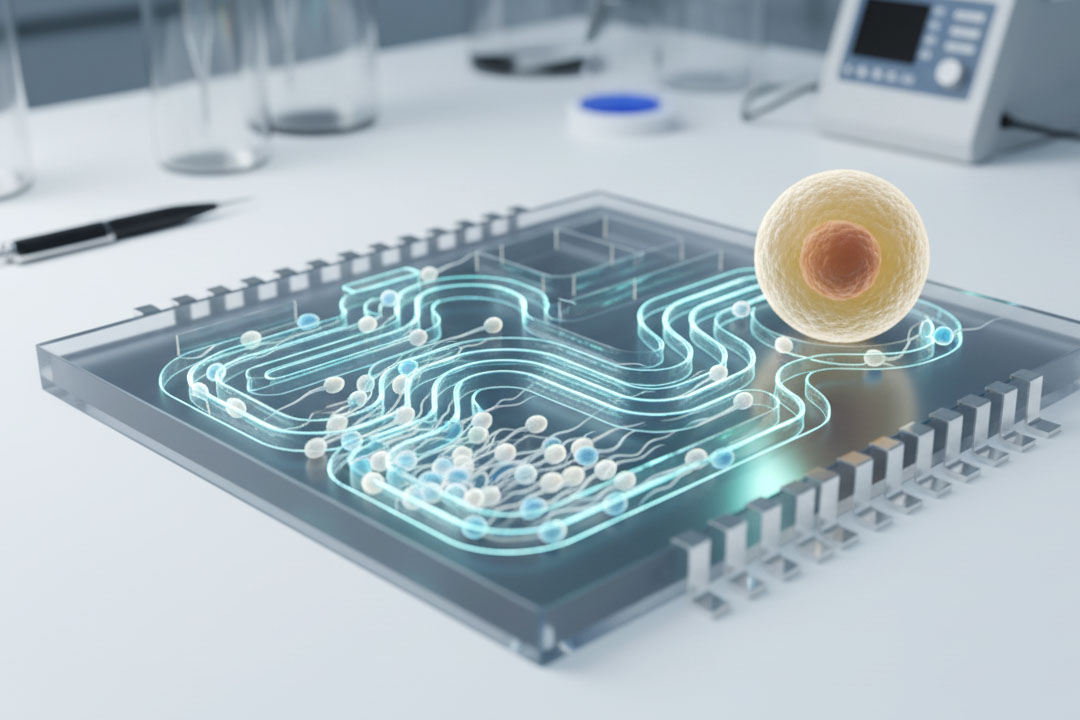

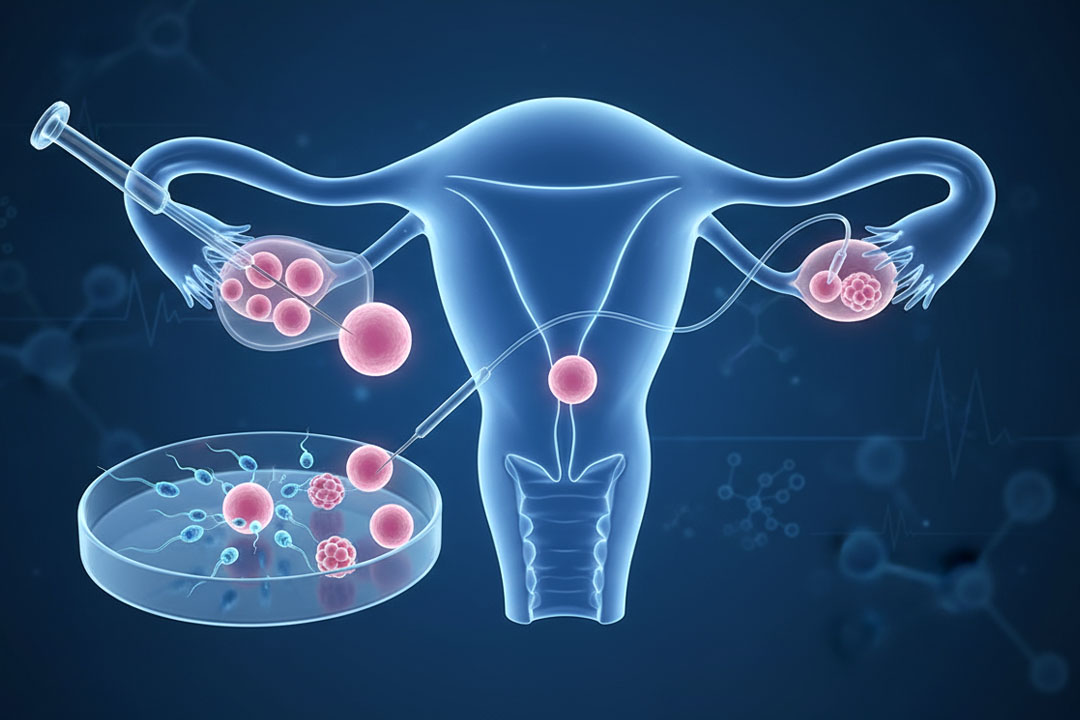

With a frozen embryo transfer (FET) the embryos are vitrified (an ultra-fast freezing step that prevents ice crystals) and stored at –196 °C. Weeks or months later, you and your doctor choose a transfer window.

Some clinics let your body lead, tracking natural ovulation while others create a “programmed” cycle with low-dose oestrogen and progesterone to build the lining and control the schedule. On the chosen day a thawed embryo is placed just as in a fresh cycle.

Because you are not recovering from stimulation, your hormone levels mimic a typical cycle, and many people find both the physical and emotional load lighter.

Are Frozen Transfers Really More Successful?

In studies that adjust for age, embryo quality, and diagnosis, frozen and fresh transfers deliver similar live-birth rates overall. Where a difference does appear, it tends to favour frozen cycles for women with polycystic ovary syndrome or a risk of ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome, while fresh cycles can edge ahead for certain low-stim protocols.

The takeaway is that success depends less on the freeze-or-not debate and more on the health of the embryo, the receptivity of the lining, and the match between the two.

Which Factors Matter More than the Transfer Type?

The biggest influencer is age at the time the embryos are created. Embryos made before the woman’s 35th birthday or from an equally young donor carry the highest chance of normal chromosomes.

Embryo grade is next: a top-quality blastocyst implants about twice as often as a poor-quality one, no matter when it is transferred.

Underlying health, especially thyroid levels, body-mass index, and uterine factors (fibroids, polyps, scarring), rounds out the top three. In short, optimize what you can like lifestyle, screening, uterine health and the choice between fresh and frozen becomes simpler.

What Unique Advantages Come with Choosing a Frozen Transfer?

Some more factors which you can consider to make a better decision are as follows:

- Flexible timing: You can press pause after retrieval, recover, and pick the moment that suits family plans or work schedules.

- Lower medication load: A thaw cycle typically needs only lining-support hormones, not high-dose stimulants.

- Chance to test embryos: Preimplantation genetic testing (PGT-A or PGT-M) requires a brief freeze while the lab analyses cells, so frozen transfer is built in.

- Reduced risk of OHSS: By giving the ovaries time to quiet down, FET nearly eliminates late-onset ovarian hyper-stimulation.

- Backup embryos for future siblings: Any extras stay safe in storage, sparing you another retrieval later on.

When Does a Fresh Transfer Become More Feasible?

If you want to go for fresh embryo transfer, consider the following:

- Younger age and limited embryos: If you produce only one or two good embryos and are under 35, transferring straight away can avoid storage fees and extra clinic visits.

- Time sensitivity: Couples travelling long distances or facing visa limits sometimes prefer to finish everything in one trip.

- Hormone tolerance: Some people feel fine during stimulation and want to keep momentum.

- Clinic protocol: A few centres report slightly higher success in specific groups, often first-time IVF patients with no PCOS when they go fresh.

How do Hormones Differ Between the Two Cycles?

Fresh cycles leave you with oestrogen and progesterone levels greater than normally present in the body from the trigger shot and luteal support. These levels are safe but not exactly natural and can occasionally reduce implantation.

Frozen cycles, whether natural or programmed, aim for physiological ranges, letting the lining develop in a calmer environment. Many patients notice fewer mood swings and less bloating in FET cycles for that reason.

What Risks or Complications Should You Be Aware of?

- Ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome (OHSS): Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is a complication of IVF treatment. It causes your ovaries to swell and leak fluid into your abdomen.

- Multiple pregnancy: tied to the number of embryos transferred, not the freeze status.

- Large-for-gestational-age babies: slightly higher after FET, close monitoring in late pregnancy helps manage this.

- Embryo survival: modern vitrification keeps thaw-survival above 95 %, yet a small loss risk remains.

- Delayed timeline: banking embryos can push the final transfer weeks or months later, which may feel stressful if you are racing the clock.

How Do You Decide Which Option Suits You Best?

Start with your medical profile like diagnosis, age, number of embryos, and prior response to medication. Layer on practical factors such as travel, finances, and work leave. Finally, consider emotional readiness.

Some people find comfort in moving swiftly, others prefer to wait between retrieval and transfer. A short conversation with your fertility team, anchored in these points, usually clarifies the choice within a single visit.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. I’m 30 and healthy—should I freeze my embryos or transfer right away?

If you have several good-quality embryos, either path offers strong odds. Transferring now avoids storage costs, while freezing buys scheduling flexibility.

2. Does freezing damage the embryo’s DNA?

Vitrification is extremely fast and prevents ice crystals. Over 95 % of embryos survive the thaw intact, and large studies show no rise in birth defects.

3. Will I need as many injections for a frozen cycle?

No. A lining-prep cycle usually involves tablets, patches, or a few progesterone shots—far fewer than a stimulation cycle.

4. Can a frozen embryo split and become twins?

Yes, identical twinning can occur with either fresh or frozen embryos, though it remains rare.

5. How long can embryos stay frozen?

Current evidence suggests embryos remain viable for at least 10–15 years, and healthy births have occurred after even longer storage.

6. If my first transfer fails, is the second try less likely to work?

Not necessarily. Many couples succeed on their second or third embryo, especially if the remaining embryos are high grade.

Conclusion

Fresh and frozen embryo transfers reach the same goal by different routes. Fresh cycles bundle retrieval and transfer into one burst of activity, ideal if you are young, have a small embryo cohort, and want to move quickly.

Frozen cycles separate the steps, lower the physical load, accommodate genetic testing, and reduce the risk of ovarian hyper-stimulation, making them appealing to anyone who values flexibility or needs extra safety margins.

Both roads can bring you to a healthy pregnancy; the key is matching the road to your medical picture and personal timetable.

Talk through the pros and cons with your specialist, trust your instincts, and choose the path that lets you step into treatment with confidence and calm.

About Us

AKsigen IVF is a premier center for advanced fertility treatments, with renowned fertility experts on our team. Specializing in IVF, ICSI, egg freezing, and other cutting-edge reproductive technologies, AKsigen IVF is committed to helping couples achieve their dream of parenthood. With personalized care and a patient-first approach, AKsigen IVF provides comprehensive fertility solutions under one roof.